Guideline 2 - Know your Building / Typical Damages / Frost Damage / Research

Frost damage

Frost damage in porous building materials such as bricks and mortar can originate from a variety of physical frost impacts, of which the volume increase of the water-to-ice phase change is the most widely known. Three conditions must be fulfilled for frost damage to occur:

The material must be sufficiently wet

The temperature must be sufficiently low, so that water in the material can freeze

The material must be sensitive to frost damage.

Frost damage is commonly solely related to aesthetical problems, particularly scaling of the exterior surface of the masonry wall, which normally not lead to structural problems except for very extreme cases. However, by adding internal insulation, the risk for structural damage may rise if the material is significantly sensitive to frost damage.

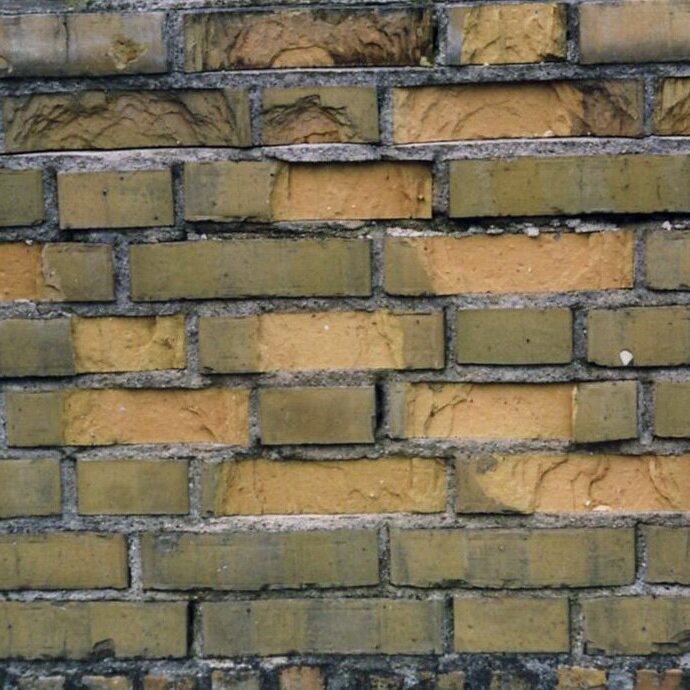

Figure 4–14 exhibits examples of scaling due to frost attack on masonry. Table 4‑7 sums up what to look for, and where to pay special attention with regard to frost damage.

Figure 4–14: Example of scaling due to frost in masonry

Table 4‑7: What to look for, and where with regard to frost damage.

Adding internal insulation to solid masonry may influence the first two conditions for frost damage to occur (wetter and colder existing wall). The wall becomes colder and conditions for freezing of water become more frequent and more intense. Furthermore, freezing will take place deeper into the wall. Secondly, it will be more difficult for the wall to dry inwards because of the internal insulation, especially in the case of using a vapour-tight insulation system, increasing the risk of critical moisture levels. However, only if the brick material is sensitive to frost damage, a colder and more wetter wall will have impact.

Porous building materials experiencing high moisture contents and low frost temperatures are at risk for frost damage. Relevant examples are ceramic brick, natural stone and mortar joint for facades of historic buildings, but frost damage may equally occur in concrete facades, roof tiles etc.

Frost damage in porous building materials can originate from a variety of physical frost impacts, of which the volume increase of the water-to-ice phase change is the most widely known. The risk of frost damage is normally highest in the outer millimetres of historic masonry walls, typically shown as scaling of the outer surfaces. Both moisture and temperature levels of porous building materials depend on the wall orientation. The prevailing direction for wind-driven rain in Europe is South-West while the lowest facade temperatures occur in North-faced facades. It is subsequently difficult to predict which is the most exposed orientation with respect to frost damage.

If there is no clear visual evidence, a direct or indirect evaluation of the masonry material could be considered, based on CEN/TS 722-22 for ceramic brick (CEN/TS 772-22, 2006) or EN 12371 for natural stone (EN 12371, 2010). If these (extreme) evaluations give a negative result, it should finally be considered to judge the sensitivity to frost damage at milder conditions with the methodology put forward by (Feng, Roels, & Janssen, 2019); one should keep in mind though that this requires an extensive experimental effort, wherein a large number of material samples has to be available.

Remedial action if damage is identified

In short, if the visual assessment reveals evidence of frost damage from the past, application of internal insulation is not recommended, as it implies that the wall is not sufficiently robust for this type of renovation.

Three conditions must be fulfilled to induce frost damage:

The material must be sufficiently wet

Phase change must happen in the material

The material must be sensitive to frost damage.

The first and second condition can primarily be affected by the type and thickness of the insulation material, but in general only a very low thermal resistance will not affect the moisture and temperature conditions, nullifying the desired impact of the thermal retrofit with internal insulation. The third condition cannot be altered in the design or the application of the internal insulation thermal retrofit. However, it can be evaluated whether it applies for the masonry material involved. As a first step, a visual inspection of the existing facade material may reveal evidence of frost damage from the past, which logically is an indicator of potential future frost damage. In these cases, the application of internal insulation should not be recommended.

^

To top